Vertical Tabs

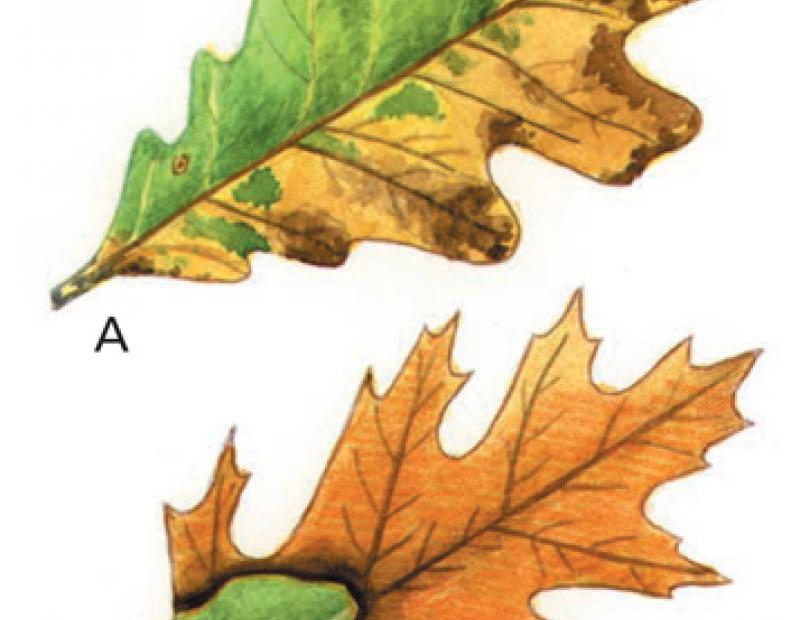

Oak wilt is a disease that affects oak trees. It is caused by Ceratocystis fagacearum, a fungus that develops in the xylem, the water carrying cells of trees. All oaks are susceptible to the fungus, but the red oak group (with pointed leaf tips) often die much faster than white oaks (rounded leaf tips). Red oaks can take from a few weeks to six months to die and they spread the disease quickly. White oaks can take years to die and have a lower risk of spreading the disease.(1)

The oak wilt fungus blocks the flow of water and nutrients from the roots to the crown, causing the leaves to wilt and fall off, usually killing the tree. Red oaks (scarlet oak, pin oak, black oak, etc.) can die within a few weeks to six months, and the disease spreads quickly from tree to tree. White oaks (bur oak, scrub oak, etc.), often take years to die and the disease usually cannot spread to additional trees.(1)

Oak wilt can be managed with a variety of strategies that prevent new infection centers and limit the expansion of existing infection centers. A good management program for oak wilt will include all of these strategies for combating the disease.(2)

Preventing New Infection Centers

Once an oak tree becomes infected with oak wilt, there is no known chemical treatment that is capable of “curing” the disease; however, fungicide research is continuing. The development of new oak wilt pockets can be avoided, however, by either preventing the development of spore mats of the fungus on diseased trees or by preventing the transfer of fungal spores to healthy trees. In practice this involves removing dead or diseased trees and avoiding injury to healthy trees.

Remove Infected Trees

Trees that are infected with or have died from oak wilt should be removed and properly treated to prevent development of spore mats. These treatments include debarking, chipping or splitting, and drying the wood. Covering dead wood with plastic, burying the edges for 6 months, and then air drying for a similar time will kill the fungus and any associated insects. Trees that die in summer should be removed and treated before the following spring, which is when new spore mats can develop. If the wood is sufficiently dried, however, spore mats will not develop.

A word of caution: Removing a diseased tree that is still living may actually facilitate the spread of the disease by accelerating the movement of the fungus into adjacent trees that are grafted to it by the roots. To avoid this problem, disrupt interconnected roots before removing living diseased trees as described in the section on “Controlling existing infection centers.”

Avoid Injuring Healthy Trees

Freshly wounded trees that are growing outside of existing oak wilt centers can be visited by beetles transporting spores of the fungus. Because open wounds create avenues for infection, damage to trees from construction, pruning, or severe storms may lead to new infection centers. Avoid injury to oaks during favorable conditions for infection, which in the North occur in spring and early summer, when spore mats are present and the beetles are flying. Favorable conditions usually occur between April 15 and July 1 in the Lake States and over a correspondingly longer period of time to the south. In Texas, avoid damage to oak trees from February through June.

Preventing injury caused by human activity is especially effective in avoiding the establishment of new infection centers. In particular, pruning or construction activities in or near oak woodlots during the susceptible period often results in injury to oak trees that leads to infection.

If construction activity, tree removal, or pruning is unavoidable, or if storms injure oak trees during the critical period, the wounds should be treated with a commercial tree paint or wound dressing. If whole trees are removed during the critical period, the stumps should also be treated with tree paint. It is very important that the fresh wounds be treated immediately because the insects that carry spores of the pathogen are often attracted to these wounds within a very short time. Tree paints are normally not recommended for general use, but using these products in this situation can protect trees from oak wilt. In the North, tree paints are not necessary if trees are wounded during the dormant season; however, judicious use during the rest of the year is recommended. From Missouri to Texas, use tree paint immediately after trees are wounded at any time of the year.

Controlling Existing Infection Centers

Once the oak wilt fungus becomes established in a stand that includes a high proportion of oak, it will often continue to spread through the grafted root systems of the trees, infecting healthy oaks.

Disrupting the connections between the roots of infected and healthy trees limits the spread of oak wilt and is an effective control measure. Infected trees and their roots will usually die before root grafts can be re-established. The oak wilt fungus does not survive in the root systems of dead trees for more than a few years.

The potential for spread of oak wilt through grafted roots is especially high after a diseased tree is removed or dies. While a diseased tree is still living and intact, there is some resistance to fungal spores moving through root grafts into the roots of healthy trees. The removal or death of a diseased tree removes this natural resistance to spore movement, and spores may then travel more freely through interconnected roots. Therefore, the timing of a root disruption treatment is critical. Roots should be disrupted before an infected tree dies or is removed, or within a short time of tree death, for maximum protection of healthy trees.

Interconnected root systems can be disrupted with a trencher, vibratory plow, or other equipment.

Trenching and Vibratory Plowing

Cutting roots with a trenching or cutting tool effectively controls the expansion of oak wilt pockets. In the Lake States, where deep and sandy or loamy soils are common, using a vibratory plow with a 5-foot blade is the preferred method of disrupting grafted root systems. The vibratory plow consists of a mechanical shaker unit with an attached blade that is pulled behind a tractor. The blade penetrates to a depth of about 5 feet, and cuts through the roots of oaks that may be grafted together. While oak roots may extend deeper than 5 feet in the soil, most root grafts are disrupted by trenching or plowing to that depth. Standard trenching tools do considerably more damage to the site, and the result is a much more apparent plow line than that caused by the vibratory plow. In Texas, shallow, rocky soils and even-layered rock often necessitate the use of a rock saw for disrupting oak roots. A chain trencher, backhoe, or ripper bar can sometimes be used. Trench depth should be about 5 feet, although this may be difficult to achieve in all situations.

The lines cut by these trenching implements are usually referred to as barrier lines. Successful disruption of root grafts to protect healthy trees close to an oak wilt infection center often requires that two or more parallel or intersecting lines be made. Primary barrier lines are those expected to have a good chance of protecting trees outside the lines. In addition, secondary barrier lines are often used to help ensure that the root graft disruption is effective. Separating groups of asymptomatic oaks from each other within the primary line may also save additional trees.

Root graft disruption can be made even more effective by removing all oak trees inside the barrier lines following plowing or trenching. Removing these trees and optionally treating the stumps with an herbicide helps ensure that all of the oak roots inside the barrier will die before root grafts can be re-established. This practice is sometimes referred to as cut to the line. Although this is a radical treatment, it may be useful in areas where oak wilt eradication is the goal. Assume that all trees removed are infected with the oak wilt fungus and destroy or treat them on site.

Stump Extraction as a Substitute for Trenching

In locations where the use of a vibratory plow or trencher is not practical because of infrastructure issues or boulder-laden soils, a strategy that involves cutting trees and uprooting the stumps may be a viable alternative. This procedure involves cutting all infected trees in an infection center as well as a buffer of nonsymptomatic trees around the infection center. Stumps of all cut trees are pulled from the ground using an excavator, which breaks many of the root connections between trees. Alternatively, trees and root systems can be pushed up and piled with a bulldozer. All cutting and stump extraction should be done during the dormant season.

This technique works best for new, smaller infection centers because the stumps can be removed before the fungus moves from the boles into the root systems of infected trees. It is also best suited to rural or forested areas where infrastructure is absent and drastic vegetative disturbance is more acceptable. If this technique is used, it is likely that followup treatments will be needed. However, this technique has proven effective where trenching or plowing is not feasible.

Chemical Root Disruption

Biocidal chemicals have been used in the past to disrupt root grafts in trees, including oaks. These chemicals are very dangerous and difficult to work with, but can sometimes be used in areas where vibratory plowing or trenching is not an option because of buried utilities and septic tanks, or steep slopes. Holes are drilled into the soil at prescribed intervals and the chemical is poured into the holes, where it diffuses into the soil and kills the roots in a localized area. These chemicals are restricted-use pesticides; they must be applied by a licensed pesticide applicator who has been trained in their use. In addition, these chemicals are costly, may damage the trees, and are effective only in uniformly textured soils where chemical distribution is even and predictable.

Chemical Control Using Fungicides

Fungicides have been developed that may be effective in preventing oak wilt when injected into living oak trees without active symptoms. A single treatment can protect red oaks from developing symptoms for 2 years following injection. In Texas live oaks, such treatments have prevented mortality in many cases, although foliar thinning usually occurs and can be substantial. Use of these fungicides is warranted when infection of high-value trees via local spread through root systems is imminent. These fungicides are apparently unable to stop already infected live oaks and red oaks from dying. Those currently available utilize some form of a chemical called propiconazole in the formulation. Such treatments create their own problems, including the necessity of wounding the tree to inject the fungicides.

The cost of the fungicide is high, so only highvalue trees should be considered for treatment. Contact your county extension office for current advice on the use of chemicals for control of oak wilt.

Effective oak wilt management programs use a variety of strategies to limit the spread of oak wilt. Some of the practices and policies that can be used in combination to effectively manage oak wilt include the following:(2)

Avoid wounding oaks during critical infection periods.

- If pruning is necessary, or if wounds occur on oak trees during the critical infection period, apply tree wound dressings or paints as soon as possible to prevent transmission of oak wilt.

- Develop and enforce construction ordinances and utility pruning guidelines that minimize wounding of oak trees.

- Use public service announcements, billboards, and flyers to raise awareness of the dangers of wounding oaks during susceptible periods.

Use a vibratory plow line, trench barriers, stump extraction, or chemical disruption of roots to isolate pockets of oak wilt.

- Communities and neighbors should join together to lower the cost of these tools and achieve more complete and effective local control.

- Use root graft disruption, use cut-to-the-line practices, and treat stumps with herbicides to greatly reduce or eradicate oak wilt in local areas.

Remove and properly treat oaks killed by oak wilt by debarking, chipping, or splitting and drying the wood before the spring following the tree’s death.

- Do not move infected wood offsite without debarking, chipping, or properly drying it. Do not move or store firewood from infected stands near healthy oaks without proper treatment.

- Use and enforce city codes and ordinances that mandate removal and treatment of dead oak trees. Such ordinances can significantly reduce the chances for overland transmission of oak wilt.

Use appropriate fungicides to protect very high-value trees at imminent risk of infection through root-to-root transmission.